David L. Hayles and Scott King

A for Infinity

August 1st - September 13th 2014

An exhibition of commissioned work by David L. Hayles & Scott King.

Author & scriptwriter Hayles presents a series of single page texts mounted onto A4 aluminium panels. Central to these sits a

mirrored pyramid structure by King that has the potential to grow infinitely. Its long title occupies multiple pages in the

accompanying ‘list of works’.

David L.Hayles, based in Folkestone, Kent, has written books including The Suicide Kit and Cannon Fodder. He is currently

adapting his novel ‘Revenge Served Raw’ into a feature film.

Scott King is an artist based in London. Recent exhibitions include Totem Motif, Between Bridges, Berlin, 2014; A room for

Nick, Lira Hotel, Turin, 2013; A Balloon for America, Bortolami Gallery, New York, 2013; Finish the work you’ve started,

Herald Street, London, 2012. Forthcoming solo exhibitions include Towers and Monuments, Spacex, Exeter & Bortolami

Gallery, New York.

Scott King, Infinite Monument (A $350 million tower to be known as the Da Vinci Tower is to be constructed in Dubai. The 68-story tower will feature floors that can be individually rotated via voice commands. Each of the floors will be constructed as a module in a factory and then fitted onto the central core. This will permit far more efficient construction and will allow the building to be erected with far less workers on site. In between floors the building has 48 horizontal wind turbines. It is estimated that, in addition to powering itself, the tower will be able to provide electricity to five other buildings of equivalent size. Construction will start later this year / When the Eiffel Tower was built in 1889 it became the tallest man-made structure in the world as well as a global cultural icon. It also became a source of jealousy in London, where architects immediately started drawing up plans to rival and outdo the Parisian landmark. Newly uncovered documents reveal an intense competition was held to find a design for what was to be called the Great Tower of London. However the building of the ambitious octagonal structure hit a stumbling block as the project ran out of money after only completing the first floor. These pictures show the amazing designs that were submitted by 68 talented architects that were published in a catalogue. Some look like carbon copies of the Eiffel Tower itself, while others resemble bizarre structures of the future. One drawing is even similar to a helter skelter and another mirrors the shape of a drill. The winning design, by Stewart, Maclaren and Dunn, received a prize of 500 guineas and according to documents was 215 feet taller than the Eiffel Tower. Paris’s Eiffel Tower was built in 1889 by Gustave Eiffel, and was originally the entrance arch to that year’s Universal Exposition– a world fair celebrating Gallic engineering. At first it was criticised as a blot on the landscape, with writers Alexandre Dumas and Guy de Maupassant among those complaining about the ‘odious column built up of riveted iron plates.’ But it was soon revered as a striking piece of modern structural art, and is now the most popular tourist attraction in the world with an entrance fee. It is by far the most prominent symbol of Paris, and indeed of French culture, featuring in countless films, documentaries, photographs and paintings. Eiffel originally had a permit to allow his tower to stand for 20 years, but it avoided being demolished after becoming a valuable communication beacon during the First World War / “There is a kind of medieval sense to it of reaching up to the sky, building the impossible. A procession, if you like … a folly that aspires to go even above the clouds and has something mythic about it.” / “Cursed be those who disturb the rest of a Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by a disease that no doctor can diagnose.” / The practice of placing hidden (subliminal) ideas in select print advertisements is a technique used by advertisers. Advertisers know that most people will not spend much time looking at print advertisements. Therefore, hidden (subliminal) ideas, imagery, and words can be placed in print advertisements without immediate detection. It is important to realize that ads are not designed for the conscious mind, they are deliberately designed to reach the subconscious mind. The subconscious mind operates under a different set of laws compared to the operations of the conscious mind. On average, people look at a print ad for no more than two seconds. Therefore the advertiser has two seconds in which to convey a message in order to increase sales. With this in mind, look closely at this advertisement and see if you notice anything interesting: This ad portrays a man smoking a cigarette at sunset. The man has built a fire and is lighting a cigarette from this fire. Ancient Egypt was ruled by kings called pharaohs. Egyptians believed that the pharaoh was a child of the gods and a god himself. The smoker in this ad represents a customer for Camel cigarettes. For J.R. Reynolds, the maker of Camel cigarettes, the customer is king / The Tower of Babel forms the focus of a story told in the Book of Genesis of the Bible. According to the story, a united humanity of the generations following the Great Flood, speaking a single language and migrating from the east, came to the land of Shinar. As the King James version of the Bible puts it: And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth. And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another›s speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth - Genesis 11:4–9 / The Tower of Babel has been associated with known structures according to some modern scholars such as Stephen L. Harris, notably the Etemenanki, a ziggurat dedicated to the Mesopotamian god Marduk by Nabopolassar, king of Babylonia (c. 610 BC).[3][4] The Great Ziggurat of Babylon›s base was square (not round), 91 metres (300 ft) in height, and demolished by Alexander the Great. A Sumerian story with some similar elements is told in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta / 2012 Olympics at Stratford, east London, to design a gargantuan tower sponsored by steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal. Like the altogether more modest Skylon – an ethereal, skypiercing mast on the South Bank designed by the architects Powell and Moya as a signpost for the 1951 Festival of Britain – Kapoor›s tower, designed in collaboration with the imaginative structural engineer Cecil Balmond, will draw attention to the Olympics Park more persuasively than any of the architecture commissioned for the event. Only Zaha Hadid›s Aquatics Centre will be able to hold anything like a flaming torch to this structure. But it does raise questions. First, when is a sculpture more of a building than an artwork? And thus, when does an artist become an architect – at least in spirit, if not in law (after all, you can›t call yourself an architect unless you have qualified as one)? And a third question, too: can artists take on architects at their own game? Long before the architectural profession was officially recognised, architects, artists, craftsmen and builders worked more or less freely across their shared discipline. The greatest of them – Michelangelo vaults to mind like some Olympian high-jumper – produced some of the finest paintings, sculptures and architecture of all time. Even by the end of the 19th Century and the early 20th, when the architectural profession was well-established, the most imaginative architects of the era were equally inspiring, whether drawing, building, painting or decorating. In Barcelona, the likes of Antoni Gaudí or Domènech i Montaner were surely artists as well as builders, as were Otto Wagner in Vienna or Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow. The watercolours Mackintosh painted in his last years in the south of France, after he had given up architecture, are quite superb. What separates the role of the artist and architect today is the fact that artists may be asked to design enormous structures requiring collaboration with engineers, yet they›re nearly always gloriously useless. Buildings have to function in matter-of-fact ways. Most need plumbing, heating, lavatories – all those down-to-earth elements that Kapoor will not have to get his head around for his soaring tower at Stratford. I›m not saying an artist can›t design a fully functioning building, any more than I am claiming that some contemporary architects aren›t great sculptors – Frank Gehry and his Bilbao Guggenheim come to mind. If you ever get the chance, do visit Diego Rivera›s House of Anáhuac in Coyoacan, Mexico City. Designed by the artist himself, this haunting 1950s structure, inspired by Mayan and Aztec architecture, houses the artist›s inspiring collection of pre-Hispanic Art. Such buildings, though, are rare. The artist brings something else to a project: unbottled imagination. Kapoor›s own Cloud Gate sculpture in Chicago›s Millennium Park – 110 tonnes of mirror-polished stainless steel – plays with infinite distorted views of the surrounding cityscape, especially its forest of skyscrapers. Here, an artist with a real love of buildings brings the two disciplines – art and architecture – into, and out of, focus. In some ways, Cloud Gate is an appealing model. There is a world of difference between a fully functioning building and an artwork designed and built on an architectural scale, but the play between the two offers any number of intriguing possibilities. Kapoor should seize this Olympian opportunity, and run like crazy / First there was the mangled rollercoaster, now for Olympian Man. Antony Gormley, the sculptor behind the Angel of the North, planned to build a 390ft naked statue of himself to tower over the London Olympics. The 40mn steel colossus would have stood next to the main athletics stadium pointing east to face the rising sun. The public would have entered Gormleys body through his feet and scaled the structure inside to reach a viewing deck in the head. Details of the giant sculpture are revealed for the first time on Sunday by The Sunday Times. Gormleys vision was the runner-up in a competition held by Boris Johnson, the mayor of London, to create an iconic work of art for the 2012 Games. The winning design, a 19m tangled knot of red steel by Anish Kapoor, was unveiled last month immediately dividing critics. The ArcelorMittal Orbit, largely funded by Lakshmi Mittal, Britain’s richest man, was variously described as a mangled rollercoaster, a mutant trombone and the Godzilla of public art. Johnson, however, said Kapoors sculpture represented the dynamism of a city coming out of recession. The mayor shied away from disclosing Gormleys design, saying the public should not attempt to second-guess the wisdom of the judges. The judging panel consisted of Johnson, Mittal and Tessa Jowell, the Olympics minister. Advisers to the judges included Sir Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate, and Julia Peyton-Jones, director of the Serpentine Gallery. Sources close to the competition said last week Gormleys entry was not chosen mainly because of its higher cost. The Olympian Man would have risen to a height just short of the Great Pyramid of Giza and was meant to represent the bond between humanity. Visitors would have scaled Gormleys effigy by lift or on foot via a staircase winding up one of the legs to a viewing platform looking out of the face. Gormley, 59, whose Angel of the North was erected alongside the A1 near Gateshead in 1998, has repeatedly used his own image in his art. Another Place, a collection of 100 life-size cast-iron figures along the shore of Crosby beach, Merseyside, has won the affection of local residents since it was installed in 2005. Similar figures popped up at landmarks in central London in 2007 and appeared again in New York last month, including one statue of Gormley at the Empire State Building. A source close to Gormley said his proposal for the Olympic Park in east London would have been spectacular. The sculpture was sublime in the true sense of the word. It was monumental, vast, awe-inspiring. I don’t think Anish’s piece is a disaster but Antony’s would have been a lot better received it had a stronger relationship with the Olympic ideal and the coming together of humanity. Art critics were less impressed this weekend. Waldemar Januszczak, of The Sunday Times, said: I feel Gormley has probably done enough plonking of figures around Britain, to be honest. I like his work, but I think Kapoor was a braver choice”), 2014, mirrored acrylic, aluminium and stainless steel, 6 of an infinite number of parts, 240 x 61 x 61cm.

David L. Hayles, requiem for a peeper, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.

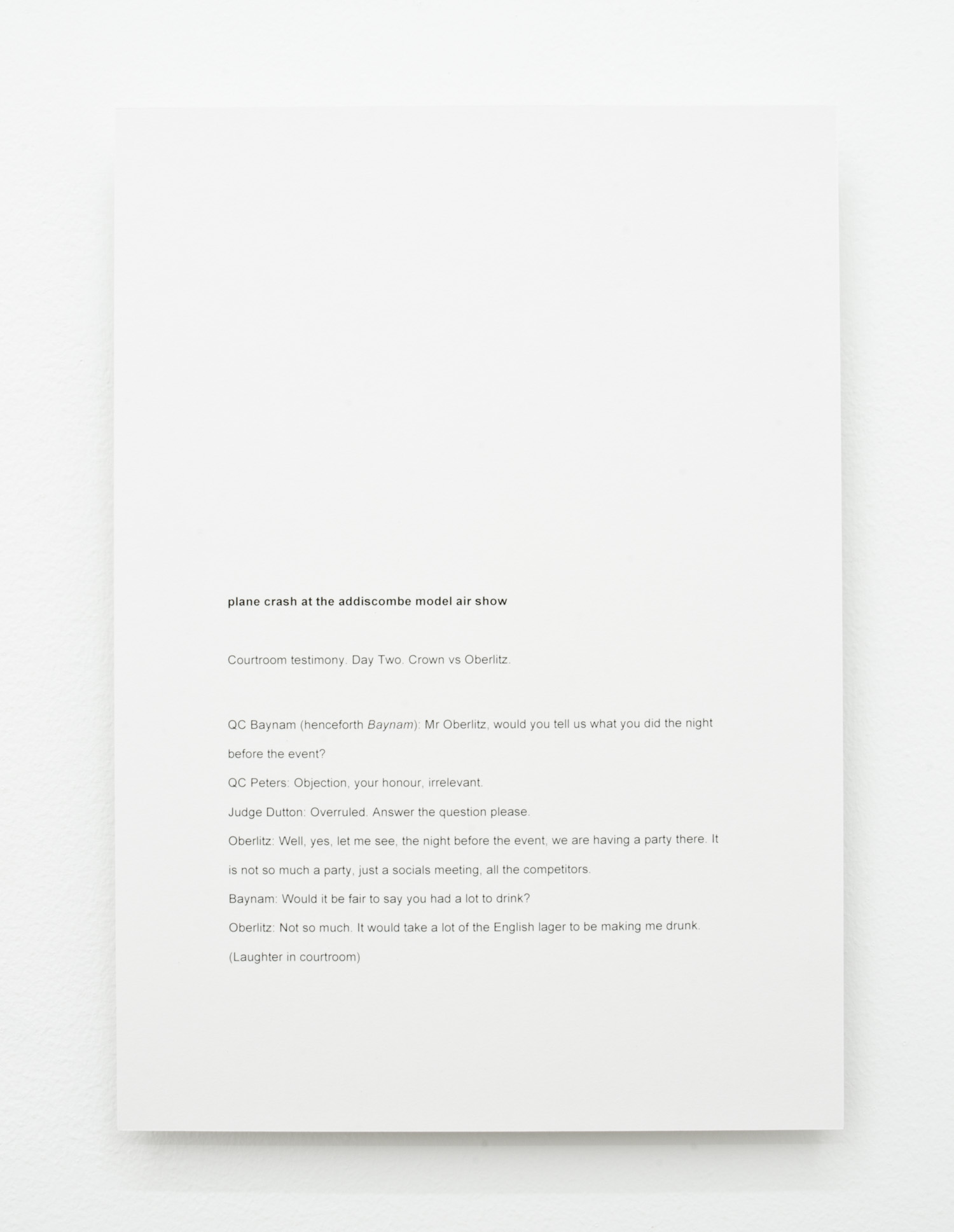

David L. Hayles, plane crash at the addiscombe model air show, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.

David L. Hayles, plane crash at the addiscombe model air show, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.

David L. Hayles, a button, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.

David L. Hayles, an unrolling, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.

David L. Hayles, worms, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.

David L. Hayles, inventory, 2014, laser print mounted on aluminium, 29.7 x 21cm.